Such are the incinerated Aragonese foothills from which Carriere’s journey begins. You can escape from the heat in the coolness of olive groves, preserved medieval peasant houses or on snow-capped Pyrenean peaks. However, the screenwriter does not stay long in Goya’s modest paternal home. The narrator moves into the magnificent palaces and quiet suites of the Prado, decorated with mature masterpieces of the painter…

Advertisement

“There was an unbearable noise in his ears all the time…” notes Carrier, describing the fatal seizure that struck the artist right in the middle of the street. — He completely lost his hearing, entering a world completely unknown to him and inexpressible — the world of total silence…” Since 1792, Goya’s work has finally been divided into the world of daytime studies and nightmares. Among the first are the immortal portraits of the artist’s secret lover, the Duchess of Alba, naked and clothed by Mahi… And at night, a silent voice seemed to whisper to him: “Don’t be afraid of what you see—look, look, notice! How grotesque are the faces and characters, crowned power, senseless battles, squalor in the midst of splendor, impotence and shame in wealth! And all this gets mixed up inside you, and haunts you, and you work in the dark, especially in the dark — with candles on your hat.”

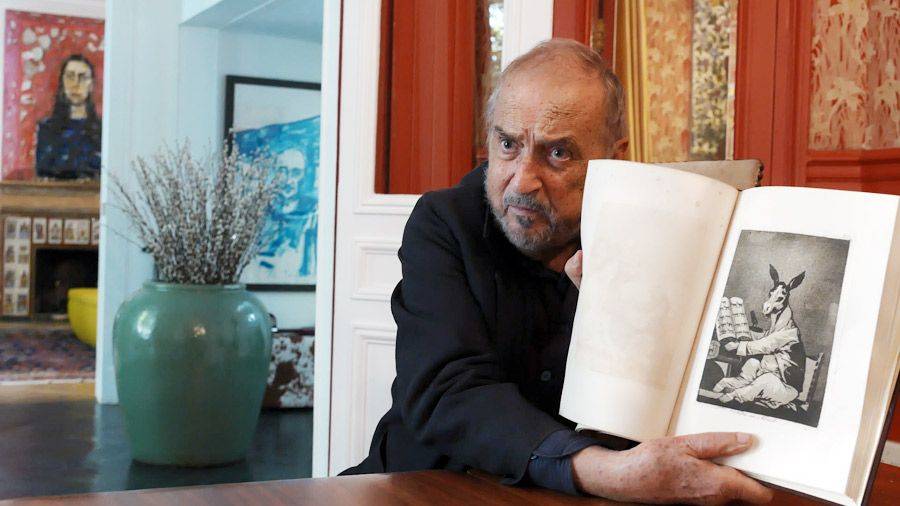

In 1799, Goya became the chief court painter and published the first series of grotesquely monstrous and exquisitely witty etchings “Capriccios”. For four years, the Madrid court was unaware of his gloomy “pranks”, then the favorite survived a semi-disaster, and soon Spain was occupied by Napoleonic troops, who inspired popular resistance and a series of prints of the “Disasters of War”.

“He was creating at the height of the French Revolution — between the old world and the new,” the narrator continues. The same circumstance characterizes Bunuel, whose half-century career has become a golden bridge over the absurd nightmares of the last century. “Bunuel and Carriere’s films are more than surrealism, they are a study of the philosophy of surrealism,” says the screenwriter’s interlocutor, director Julian Schnabel, “they have a greater spatial scope, in contact with Goya’s paintings. The latter are by no means easel paintings, rather they are movie screens!” And then he makes a reservation: the artist and the director “differ in that Goya had a fantastic imagination with demons and witches, all this hardly interested Louis. In his mind, demons are the essence of men and women. They do not belong to another world, namely ours, and behind the scenes of their scene with its absurdity there is something real. In his revelation is the power of Goya and Bunuel.”